The 58th anniversary of the first military coup of the republican era that continues to haunt Turkish psyche was marked yesterday.

On May 27, 1960, a group of 37 relatively low-ranking officers instigated a military coup to topple the Democrat Party (DP) government, which had been in power since 1950. They accused the government led by Adnan Menderes of leading Turkey to a regime of oppression and down a path of political turmoil.

The DP, under the leadership of Menderes, was the first democratically elected party to win the elections in the republic's history.

The Republican People's Party (CHP), established by the Turkish Republic's founder Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, had ruled the country since the founding of the country in 1923 until 1950.

The DP won the 1950 elections with more than half the vote. Its socio-economic policies helped the party to cement its success in the 1954 and 1957 elections.

Nevertheless, anti-government protests gained momentum and student riots at universities led to the declaration of martial law. The main opposition CHP, chaired by the country's second president, İsmet İnönü, was the government's strongest critic, and eventful CHP rallies further fueled tensions between the CHP and DP.

The CHP is accused of inciting unrest among the public against what it called the dictatorship of the Menderes government.

On May 21, 1960, a group of cadets from the Turkish Armed Forces War Academy took to the streets, which marked the first sign of the upcoming coup.

Six days after the cadets' "silent march," a group of mid-ranking military officers calling themselves the National Unity Committee declared the coup, removing the government and dissolving Parliament.

Despite arresting the chief of the general staff, the coup plotters encountered significant opposition from generals, one of whom announced his intention to come to Ankara at the head of his army to arrest the plotters if the coup regime was not headed by a senior military officer.

As a result, the retired Gen. Cemal Gürsel was recruited to head the coup regime, which pushed into retirement 235 generals and 3,500 lower officers and 520 judges and prosecutors in an attempt to place both the military and the judiciary under its control. All government officials from Menderes down were detained.

Prime Minister Adnan Menderes was the first democratically elected head of government of the Republican era.

In a coup declaration broadcast on the radio, the coup leaders said, "A crisis of democracy and public unrest forced the Turkish Armed Forces to take over the rule of the country against a likely civil war."

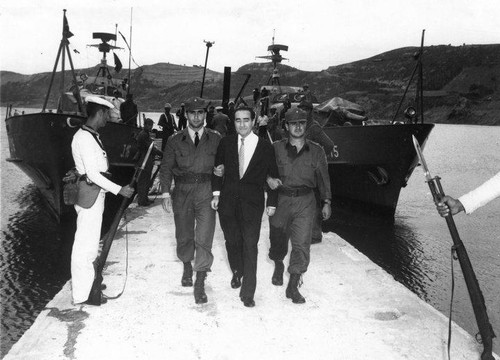

The coup also marked the beginning of what many see as the darkest page in Turkey's history. Menderes, the first prime minister of the country elected democratically, was hanged after the Yassıada Trials, named after an island in the Marmara Sea where the trial took place.

Menderes and his Cabinet members, President Celal Bayar, DP lawmakers, Chief of Staff Rüştü Erdelhun, some top military officers opposing the coup and bureaucrats were detained. Menderes and his colleagues were charged with crimes, including high treason and misuse of public funds, and were subsequently arrested. They were imprisoned on Yassıada where they stood trial between October 1960 and September 1961. Then Foreign Minister Fatin Rüştü Zorlu and Finance Minister Hasan Polatkan were hanged on Sept. 16, 1961, and Menderes was hanged a day later.

Today, Yassıada, a symbol of the coup, is undergoing a renovation as part of the "democracy island" project. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan's recent election manifesto underlined this intention to implement this project. There, a monument in memory of Menderes, Zorlu, Polatkan and other hanged politicians is planned to be erected.

As for the late politicians, Parliament passed a law in 1990 that restored their honor and enabled the transfer of their bodies, which were buried on another island, to graves located under a monument dedicated to them in Istanbul.

This coup also began an era of serious coercion on democratically-elected politicians by military officers who saw themselves as the self-appointed guardians of the Republic. The coup encouraged future military interventions in 1971, 1980 and 1997, as the military, the self-proclaimed defender of the Republic, intervened in the country's governance at times when it saw it as necessary, especially when the broadly interpreted secularism of the country and public safety were considered to be in danger.

The 1971, 1980 and 1997 coups respected the internal military hierarchy, headed by the chief of the general staff.

The 1980 coup was justified by the chaos brought by clashes between left-wing and right-wing movements, though it only served to marginalize people further after conducting a brutal crackdown and executing people from both groups.

Just as the country was seeking to escape the clutches of military tutelage by electing a party catering to the conservative population, the military managed to oust the government in 1997 by threatening a coup. The only military coup that failed was the one instigated by the Gülenist Terror Group (FETÖ) on July 15, 2016.