Laurent Cantet's 2017 film "L'Atelier" is about a writing workshop organized by the municipality of La Ciotat, a once grand shipping town on the Mediterranean coast. The young people attending the workshop are pretty representative of modern France: white, brown and black. Their task is to write a story together, and as in any group, some of them are more eager to "play" than others. When their female, white, Parisian tutor encourages them to come up with ideas to start off the storytelling, it is Malika who is most forthcoming, and she suggests that they write a murder story. Thus, Cantet introduces narrative tension, both for the story that the young people will be telling and his own.

Cinematically speaking, there are almost no "beautiful shots" or technical tricks to engage the viewer. As far as Mediterranean coastal towns go, La Ciotat is no beauty, and Cantet does not try to convince you otherwise. As the tutor also points out, the now almost defunct port towers above the town, determining its character. The one "beach" we get to see is actually a rock promontory from which we see one of the participants dive into the dark blue choppy water - nothing like the Mediterranean we are used to seeing in travel brochures.

As in the French tradition that has now become a much-mocked stereotype, it is in the conversations that Olivia, the tutor, has with her students that the story and the tension of the film is sustained. The initial tension is between the Parisian Olivia and the participants who find her snobbish, but gradually, as some of the young people decide to work with her, other tensions rise to the surface. Yes, you're right: racial tensions. The first moment comes when Malika suggests that the murder take place in the port, as the port is indeed crucial to the history of the town. It was to work in the port that her grandfather came from North Africa she says and that is how she ended up being French. Fadi, with his beard as thin as a sculpted eyebrow, stretching from ear to ear, mocks her in Arabic when she says she is French. They exchange a few good-humored salvos when the black Boubacar intervenes, saying Arabs are ever ready to fight.

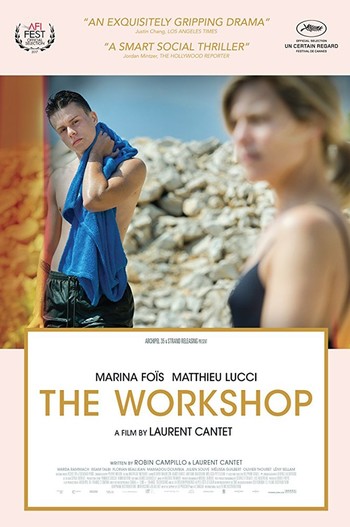

While the more verbose of the group are thus keeping the project going, it is clear to the audience that the film is really not about these bright brown and black people but the more quiet white boy whose home life we have already had glimpses of. This is not the film for you if you're looking for a non-white protagonist. We see him, Antoine, simmering as the others talk about the city and its identity, and whenever he speaks, Antoine concentrates on the violence that the murderer will unleash on his victims. The others, including the other white boy Etienne, are a bit unnerved by his attitude. While the rest of the group go down town to their homes together, Antoine prefers to hone his diving skills, filming himself as he does so. We see him working out, grooming himself and spending time on his computer; yes, you've guessed it, watching anti-immigrant videos. He is, however, at the same time, shown to be good with children, and in fact a moderating voice in his rather irresponsible friend circle.Back at the workshop, when participants share what they have written, Antoine's is revealed to be the bloodiest.

When Fadi objects to so much violence being included in the communal story they are supposed to be writing, Antoine responds by asking whether he means the kind of violence that Fadi's friends have unleashed in Bataclan. At this point, even as an audience member I feel a sharp pang of injustice, that young people who have no connection to a particular crime should have to deal with such cavalier imputations day in, day out. It almost comes to blows when Olivia intervenes, and invites the group to try to consider Antoine's passage in literary terms, its ability to invoke a certain scene, adding that it is a shame that Antoine is putting all his efforts in describing the horrid. In these workshop scenes there is actually much to entertain those who are interested in the art of writing. We are, however, drawn to content, and Antoine's unwelcome remarks about violence add up to an understanding that the instinct of violence comes first, then comes the object of that violence. This is, of course, a conciliatory note of sorts: It is not because the terrorists hated the "Western way of life" that they attacked Bataclan, they wanted to lash out with violence and a hatred for the "Western way of life" seemed as good an excuse as any.

In that sense, all this racial tension in the workshop itself seems to be a ruse for something else that the director seems more interested in and that is the relationship between Olivia and Antoine. We watch Olivia watch Antoine and "understand" this white underprivileged boy's fears and desires. He is the embodiment of a certain kind of youth, and wouldn't you know it, Olivia is having a difficult time fleshing out a young male character in the novel she is working on. So, with Olivia, we scrutinize Antoine here and go on his Facebook account to see what kind of a life he leads. Antoine, for his part, is equally intrigued by this successful, urban woman. He even buys one of her books to read - the only workshop participant we see doing so in the film. He watches her interviews and is even teased by his friends that he is attracted to her, a suggestion he brushes away demurely.

However, the idea of sexual tension is placed in the viewer's mind, and it is mightily enhanced as we climb up a tree outside Olivia's house with Antoine to spy on her evening routine. We watch with him as she walks from one room to another in her undergarments, holding the laptop in her hand - as she herself is spying on him, looking at his Facebook profile. It is a strange register of consummation, a connection that the film will take further towards the end when Cantet makes a concession to his dialogue driven film and launches us into a moonlit night by the water. It is in this crucial scene that La Ciotat, port and all seem idyllic, in a light that Antoine also admits he has not seen before. It is also in this scene that Antoine manages to take the upper hand in a reversal of power: Hoping to mine Antoine's life for details for her fictional character, Olivia herself becomes the symbol of the established order that will now have to answer to Antoine. If I were uncharitable I would say that it is the white boy's dreams fulfilled: He has given a piece of his mind both to the brown people and the older white female.

However, I am charitable, for I too find something mesmeric in Antoine's simmering dissatisfaction, a belief that if I work out the code of his behavior, I will have worked out the foundations of "white rage." Cantet lets us spy on Antoine for a while and teases us with hints about what makes Antoine tick. But, at least for me, Antoine remains a cypher throughout - despite the "happy end" that Cantet thinks fit to give to him in the end.

*Nagihan Halıoğlu / Daily Sabah